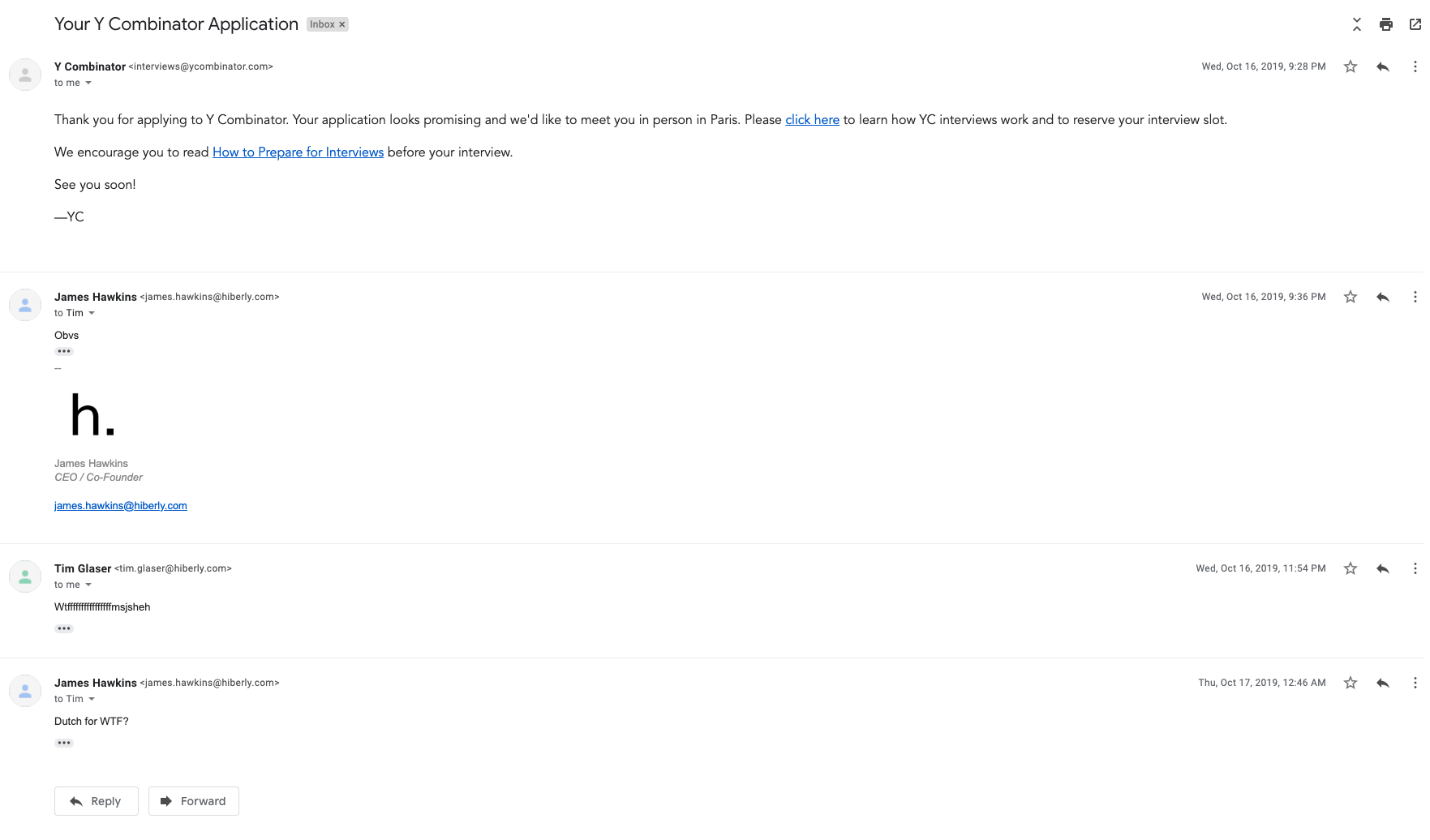

We submitted the application, then got back to work. We couldn't work out how long it'd take to hear back, but then we did.

It was now October 16th. The interview was going to be November 7th.

We asked ourselves how we could make as much progress as possible between now and then.

Best case scenario, we'd get some paying customers. Worst case, we needed to show we had made a ton of progress.

Walking between meetings, we felt we had two plays. The first that came to mind was a Hacker News "show HN" post. That website is read by tens of thousands of developers, so to us represented a huge volume of relevant traffic.

We decided that was too risky - it'd be binary, either a couple of upvotes or a hundred. We felt the most likely outcome was that we'd get five upvotes from our friends and that would probably leave us with nothing to talk about if we put all our focus into it.

Instead, we worked out that if we could find a repeatable approach to generating users, we were guaranteed to be able to make progress. That felt achievable.

We took $2K of our $8K and set up ad campaigns on every display network - because there aren't many other platforms that tackle tech debt, so search traffic doesn't exist, yet.

We started getting a trickle of leads. They all bounced.

We put in place product tracking - we put UTM tags into every ad, so we'd know exactly which users came from which ad and each channel. We started putting more of our spend into the channels that worked.

We started experimenting with the website layout until more visitors installed the app, then we started tweaking the sign up process until people were starting to use it, then we started tweaking the product further until people were using it a lot. We just treated the whole thing and all our product development as a funnel.

In parallel, I'd email every single user who signed up, trying to learn from them. Almost no one spoke to us. You can find a lot out from data, but it's no substitute for the real thing. Developers are much less likely to take a call than salespeople from our previous experience.

We kept up the two meetings a day target, but often missed it. Engineering leaders were harder to get in front of than sales leaders.

The week before, we booked practice sessions with everyone we thought was relevant. This meant friends, family, a VC and two YC alumni who were offering to do this on Twitter.

We made these sessions realistic - we told them to cut us off, to interrupt if we weren't getting to the point, and to trip us up.

We focused on clarity. We had achieved a lot fast. We had signed up 400 people in just three weeks, for $10 per user (the cost came down a lot per user after a lot of tweaking, so the more recent ones were way less expensive). Given we'd charge $10 per month per user, the unit economics looked really good. We hadn't yet generated revenue, but we had 2 companies who said they would pay (and, a few weeks after the interview, they both did, which got us to our first $600 MRR).

Tim and I got the Eurostar from Kings Cross to France the night before. That evening, we went out for a beer and caught up with an old friend.

November the 7th swung around before we knew it. We did a final run through in the morning, wrote out some key stats on a notepad to take into the interview in case we needed them, and tried to catch each other out - we, finally, felt like we had a good shot at this.

We began the blustery but bright walk from our hotel to Front's offices, who were hosting it.

We walked in, got our badges and did our best to ignore everyone else. We were led into the room by Dalton Cadwell. He was the first person I'd met in real life that I already recognized from YouTube. Geoff Ralston, who also interviewed us, was the second. There was one other person who remained quiet.

The questions came thick and fast as soon as we started shaking hands, but the tone was bright, excited and helpful. We had a clear view of who would answer different types of question, which was important. The key thing we focused on was making ourselves pause before answering, and we took the time we needed to be clear. We'd endlessly rehearsed explaining what we do "off guard", so we wouldn't get caught out.

As we left, literally as the door was shutting, we were asked who we were. It's important you can describe your relevant experience as concisely as you can describe the product.

All of the questions went well, but we felt we didn't manage to answer one along the lines of "how could you show that you have solved this problem for a real user?" They asked us for a demo to see the data we had generated but we hadn't got the laptop connected to the wifi. There wasn't time.

Note: later on, now we come to write this, that precisely why we ended up pivoting. They're good.

We walked out thinking it's 50:50, we did a good job but got that question wrong, and we got hung up on it right at the end.

We grabbed a quick lunch then went to the nearest WeWork and got back to working. Tim found a guitar, the latest way to distract people who are coworking, it seems:

For this interview, we knew in advance we wouldn't find out for a few days, so we decided to assume we had failed. We met with friends again and got the train back to London.

That magical phone call came around a week later. Dalton called asking us to accept. We both were in the office, so it was nice to be able to listen to it together. We called our friends and family, and promised ourselves this was just the start. We had to make the most of this opportunity.

The weeks that followed were quite stressful. We suddenly had to find a lawyer to create a US parent company, we had to book an Airbnb, and work out if we needed an accountant, whilst still keeping the company growing and signing our first clients.

We immediately started doing regular calls with the partners and we chose to send a regular update once a week with our progress. Knowing this was coming up every Friday kept our urgency up.

Enjoyed this? Subscribe to our newsletter to hear more from us twice a month!